PIT Tags and Passive

Antenna Systems Part 2: Arctic Adaptability

Greg Hill, Florida

International University

Hi Folks,

Last post I discussed the use of PIT

tags and Passive antenna systems (PAS) in studying fish movement and fine scale

habitat selection of Everglades sunfishes at an experimental facility. In this post I’m going to talk about scaling

up the application of PAS- at both spatial and latitudinal gradients.

While this technology can be very

effective at monitoring an organisms use of one habitat patch or another (Such

as in my first blog post), another major area of research which employs PAS is

anadromous fish migration. There is an extensive

body of literature from the Pacific Northwest detailing the use of PIT

technology in studying salmonid spawning, survival and migration. More recently this technology has also show

its versatility and hardiness in extreme environments- such as arctic tundra

river systems.

Last summer (or fall in arctic time)

I was fortunate enough to be a part of a study examining arctic grayling adaptability

to climate change. “FISHSCAPE” is a

Woods Hole Institute project led by Principle Investigators Linda Deegan (MBL

at Woods Hole) and Mark Urban (Uconn) that conducts its research out of Toolik

field station on Alaska’s North Slope.

Here the project’s focus was on 3 river systems of different size,

gradient, thermal regimes, and seasonal connectivity. By better understanding the growth, movement

patterns, and genetic linkages of arctic grayling in each system, FISHSCAPE

hopes to shed light on the impact of shifting seasonality in arctic aquatic

ecosystems.

Toolik Field Station:

Established in 1976 as an extension International Biological Program, TFS has become a premier research base for arctic science. Now managed by the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, TFS has cooperative agreements with a number of agencies and Universities which support numerous studies to help better understand the arctic environment and its impact at the global scale. Just getting to TFS can be quite an adventure. Its location just off the Dalton Highway on the North Slope of the Brooks Mountain range puts 357 miles north of the nearest city (Fairbanks) and 117 miles south of the Arctic Ocean. Researchers here enjoy round the clock sunlight from May 26 to July 17- but never see the sun rise from November 27 to January 14. However, the Aurora Borealis does provide its own magical lighting once night returns to the arctic.

Arctic Grayling (Thymallus arcticus)

Arctic

grayling are a circumpolar member of the salmonid family that is widespread

throughout the arctic and subarctic regions of the world. They are long lived (20+ years), can grow up

to lengths of 24 inches, and are easily distinguished from other salmonids by

their exceptionally large dorsal fin and small mouth. When looked at closely in the water they

exhibit a mixture of iridescent colors that seem to shimmer in sunlight. I would describe their appearance in the

water as almost “electric”. Primarily

insectivorous, they are beloved by fly fishermen for their enthusiasm to take

dry flies. Grayling are also a vital part

of biotic linkages in arctic aquatic ecosystems. As spring spawners, their seasonal movements

between productive riverine habitats and overwintering areas such as headwater

lakes or spring pools play a large role in nutrient transfer and diet

subsidization for other organisms- especially other fish such as lake trout and

arctic char.

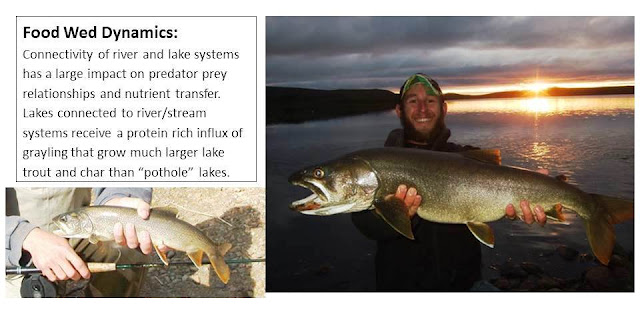

Importance of Biotic

Linkages

PIT tagging and PAS setup on the

North Slope:

An extreme environment such as the

arctic presents a number of unique factors that must be dealt with accordingly

in order to achieve continuous monitoring of fish movements across the

seasons. First off, the rivers flowing

out of the Brooks Range are very low in conductivity which makes electrofishing

difficult. Fortunately, the voracious

appetites of arctic grayling awakening from a long winter’s slumber make them

fairly easy to catch with angling techniques.

Small spinners and flies with barbless hooks are also less harmful and

easily removable. With a team of 2-4

anglers it is not uncommon to capture and tag over 100 grayling in a single

day! A weir built at the outlet of a

headwater lake in the fall is another effective method for fish capture as they

migrate back to overwinter.

We

used both 12 & 23 mm half duplex PIT tags since each size provided its owe

advantages. 12 mm tags allowed us to tag

much smaller specimens but did not afford the same detection range as the 23 mm

tags. The mesh holding pens we used

while processing & tagging fish needed to be carefully placed and easily

movable as conditions in some rivers could change to flood stage rapidly depending

upon weather.

With many PAS stations set up at points along river sections only accessible via helicopter or snow machine, a solar power provides a reliable means of keeping the equipment running year round. Three properly angled 100-watt panels are able to harness and store enough energy from the arctic summer sun to keep a series of car batteries charged and supplying power to the reader & antenna system even through the dark winter months- Keeping this setup protected from wildlife and the elements in another matter.

Heavy duty army ammo boxes lined with Styrofoam help keep the readers and batteries protected and insulated from the elements. The local wildlife, however, has been found to be quite fond of messing with the solar panels and electrical wire connected to them and the antenna. Grizzly bears seem to enjoy tearing apart the solar panels while arctic ground squirrels or “sik sik’s” have a habit of gnawing on wire. Project coordinator Cam Mackenzie has found that erecting a small electric bear fence around the panels and adding thick metal shielding to the wires and cable deters these tundra residents fairly well- Not exactly your everyday troubleshooting!

The arctic may be a difficult place to work in at times, but its raw beauty and importance in understanding climate change are well worth the challenges. Hope you’ve enjoyed both posts on adapting passive antenna systems to the top and bottom of America.

Greg Hill

Masters Student

Florida International University

No comments:

Post a Comment